Landings

by

Posted

Introduction

I must say, it’s tricky to teach people to land. Most manoeuvres that you have to learn in order to be a pilot can be practiced thousands of feet up in the air, where there’s no danger and no damage if things don’t work out, and where the instructor has plenty of time to fix things if and when they go wrong. The instructor can repeat exercises again and again, letting the student mess things up as they find their own way to perfection.

However, for reasons that should be obvious, botching a landing while learning can have serious consequences!

Let’s try to break down how to land a small airplane into manageable chunks and see if that makes it easier to learn.

1. The approach

Important principle: a good landing begins with a good approach.

If the approach isn’t set up right it becomes much harder to perform a good landing.

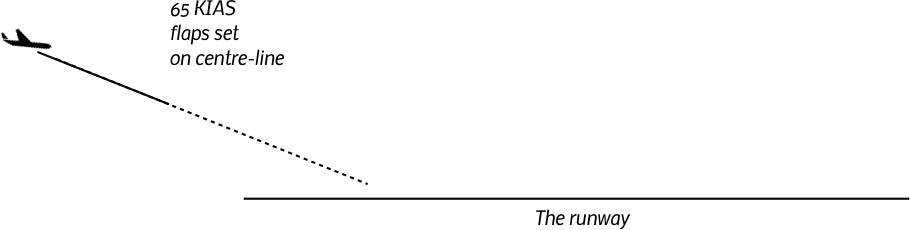

A good approach can begin in a variety of places, but it ends with the aircraft:

- at 70 knots indicated airspeed (if you’re in the Grob)

- positioned on the extended runway centre-line

- moving parallel to the runway centre-line

- and aligned (longitudinal axis) along the centre-line,

- with the flaps extended as desired (typically full flaps),

- and with the throttle at a low power setting – typically 1500rpm or fewer

- descending towards a suitable point near the threshold of the runway

- and descending at a moderate rate, say 500fpm, depending on circumstances

- with the aircraft in trim. (Very important!)

Note that items 2, 3 and 4 above may involve the application of some crosswind corrections (wing down on one side combined with opposite rudder). I’m not writing about crosswind landings specifically, but everything here applies to those too.

There are many ways to arrive at this situation, and from the point of view of a good landing, they’re all equivalent:

You can slow down to 70 knots four miles out from the runway. Or you can come screaming in at 130 knots until one quarter mile final, then pitch up, drop full flaps, and sideslip down to the perfect place slowing to the perfect speed as you relax the sideslip.

Or you can use some middle-of-the-road speeds and settings that don’t involve sudden power or configuration changes or long periods flying very very slowly. But that’s really a matter of style. As long as, at the end of the approach, you set yourself up as described, you will make the job of landing as easy as possible.

2. The roundout

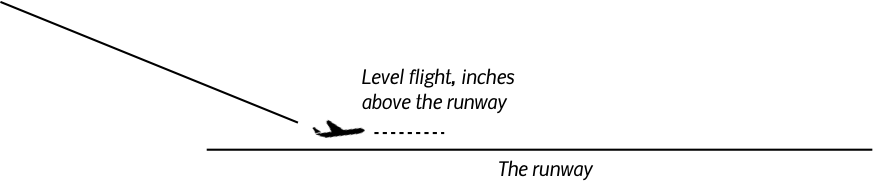

Important principle: fly parallel with the ground, at a height of a foot or six inches.

During the roundout you should bring the aircraft to level flight, parallel with the ground, flying along the runway centre-line, and keeping the airplane aligned with the centre-line too.

The transition from the descent to level flight is tricky because your height above the ground when you get to level flight is very important: if you roundout too high the eventual touchdown is likely to be “firm”, or worse, and if you try to round out too low, you will strike the runway with the nose wheel instead.

In this phase you are trying to skim the ground, at what seems an impossibly low height. The pilot having spent the last hour concentrating on keeping the plane thousands of feet up in the air, it’s easy to become “ground-shy” and roundout several feet up in the air. At this point recall (if you can) the view of the airplane just before you left the ground on takeoff. You are trying to achieve a sight-picture from only a foot or so higher in the air than that.

At this time it also helps to direct your attention forward to where the runway motion ceases to be blurred – typically five hundred feet ahead of the aircraft. If you look too close in you have very little height perception.

3.The hold-off

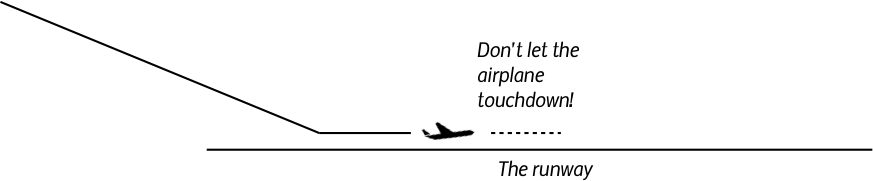

Important principle: Don’t let the airplane land!

At the start of the next phase of landing, the hold-off, reduce the throttle to idle. (I recommend you don’t do this any earlier, while learning.) Now keep the airplane in level flight at the same one foot or six inches above the ground, by pulling smoothly back on the yoke to increase the pitch angle as the aircraft bleeds off airspeed. You are working against the aircraft’s natural tendency to sink by raising the nose at just the right rate.

Very soon you should start to hear the stall warning horn, and, more or less simultaneously, the airplane will settle softly onto the runway on the wheels of the main undercarriage.

It’s quite common during the hold-off for the pilot to pull back too quickly on the yoke, causing the airplane to balloon up in the air.1 Recognizing that this is an error, depending on the size of the balloon, there are three things you can do:

- If it’s a small balloon – just a foot or two of height gained – freeze the yoke. The airplane will go up, then start to come down again. As it starts to descend, arrest the descent by starting to pull back on the yoke again. Then continue with the effort of trying to prevent the airplane from landing.

- If it’s a medium-sized balloon, freeze the yoke and add a small increment of power with the throttle – say to about 1200 or 1300 rpm. This will cushion the descent back to the right hold-off height, and you can continue to pull back on the yoke from there. After the airplane touches down, reduce the throttle to idle.

- If it’s a big balloon (say 10 feet or more in height) – it’s not worth trying to save the landing. The risk of a stall up in the air followed by a pancake onto the ground is too high. Add full power, manage the pitch carefully and when you have a safe airspeed pull up, and go around.

Be aware that a poor response to a balloon is to push forward on the yoke. This is tempting, because, after all, pulling back too much made you go up, so pushing forward again should make you go down, right? Unfortunately this is the recipe for an (at best) very heavy landing. Don’t do it.

4. The rollout

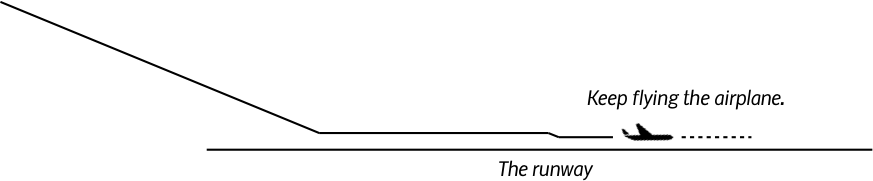

Important principle: keep flying the plane, even after it’s on the ground.

Many landing accidents happen during this phase of flight. (I read about two such accidents, both to big airliners, just yesterday.)

Eventually the airplane will slow enough during the hold-off that it has to touch down. At that point, it’s vital that you keep flying the airplane. At the speed at which it is moving, the wings still generate enough lift to keep most of the weight off the wheels. Maintain your concentration and control inputs to keep it on the centre-line and travelling along the centre-line.

Allow the nose-wheel to descend gently to the runway, after the main gear is fully in contact with the ground.

The transition to from flying machine to rolling along on the wheels can be tricky. Strong crosswinds make it more so. At landing speeds the flight controls (especially the rudder and ailerons) remain quite effective. At taxi speeds, the nosewheel steering is helpful. At in-between speeds you need good concentration to maintain control with both flight controls, nosewheel steering, and maybe some braking.

During initial phases of learning, don’t try to clean up the plane (raise the flaps, retune the radio, etc) until you have established positive nosewheel steering and are exiting the runway.

Quiz

Answering a few questions on material you’ve just read is a good way to cement learning. Here’s a short quiz, to which all the answers are on this page. There are no prizes – but just thinking about the questions in order to answer them is a good exercise.