Under, over, or around those clouds?

by

Posted

If you do an amount of cross-country VFR flying eventually you’ll come across a situation where your airplane is headed what looks like right at a bunch of clouds. It can be helpful to know a few minutes in advance, whether, when you reach the clouds they’re going to be at your altitude, or whether you’re going to pass above or below them.

Initially you might think that since your airplane (in level flight) is flying towards the horizon in front of you, if the clouds obscure the horizon then you’ll have to go up, down, or around, or alternatively if you can see the horizon clear ahead that you will pass over or under them. However, depending on your height above the ground, things aren’t quite that simple.

Depression of the horizon

Pilots will certainly remember that the higher you fly the further away the horizon is, and holders of a commercial pilot licence will remember that VHF range at a given altitude is approximately the distance to the horizon for which a formula is 1.22 times the square root of your height above ground level in feet. For example if you’re 3600 feet AGL then the horizon is 1.22 x 60 = 73.2 miles away.

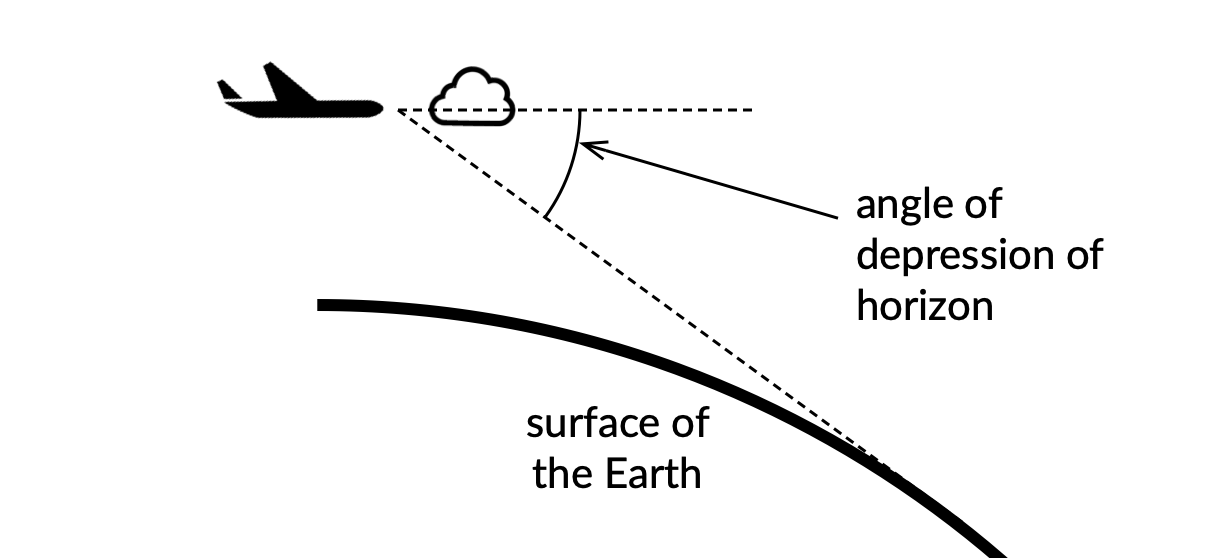

Another feature of the distance horizon is that it appears to be below the horizontal. So if you’re within a few miles of a cloud that’s at your altitude it’s entirely possible you can see the horizon underneath it:

Angle of depression depends on your height

The higher you fly, the further down you have to look to see the horizon. (Imagine you were on the International Space Station, looking down at the planet underneath you. Then the horizon would be very “down” in all directions!). A little fiddling about with trigonometry and you can work out that for heights above ground that are small compared to the radius of the Earth (which itself is close to 21 million feet) the depression of the horizon in degrees is about the square root of the height above ground (in feet) divided by 57. So how does this work out at different altitudes?

- At 3600 feet agl, the horizon depression is about 1 degree, and the horizon is about 73 nautical miles away

- At 7500 feet agl, the horizon depression is about 1.9 degrees, and the horizon is about 130 nautical miles away

- At 15,500 feet agl, the horizon depression is about 2.2 degrees, and the horizon is about 150 nautical miles away

What that means is that when you’re in level flight, the direction you’re actually travelling is (depending on your altitude) something like one or two degrees above the horizon as it appears from the airplane. If there’s a nearby cloud ahead that looks to be above the horizon by a degree or two, you are likely heading directly towards it.

How can you measure small angles against the horizon?

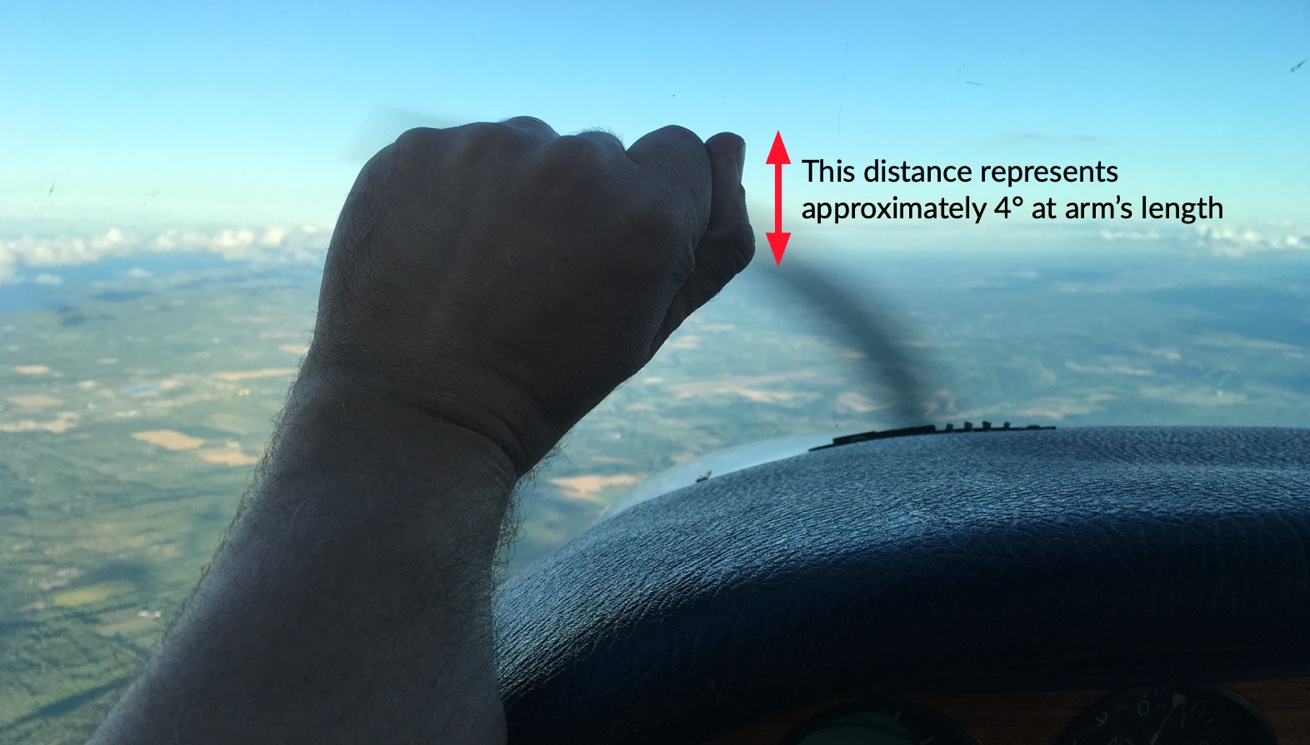

You might think that being able to look ahead and determine where one or two degrees above the horizon is, is a difficult or fiddly task, but in fact there’s a very easy way to do it. For most people, the knuckle of their thumb subtends about four degrees of arc at arm’s length. In other words if you hold your arm straight out in front of you so the last joint of your thumb points up in the air, then angle made by your thumb tip is about 4 degrees. (I owe another shout-out to Prof. John Denker for that tip. No pun intended.) You can easily use this as a kind of ruler in flight to see where your airplane is headed:

If you don’t want to use your thumb, you can use the second joint of your first finger, which is about the same length.

Another use for this little trick is to judge your approach angle to a runway – perhaps that will be the topic of another post. In the context of this post however you can use it to get a little earlier advance warning of whether you should start to climb or descend to avoid some clouds ahead, or whether you can keep your altitude and clear over or under them.