Checklists

by

Posted

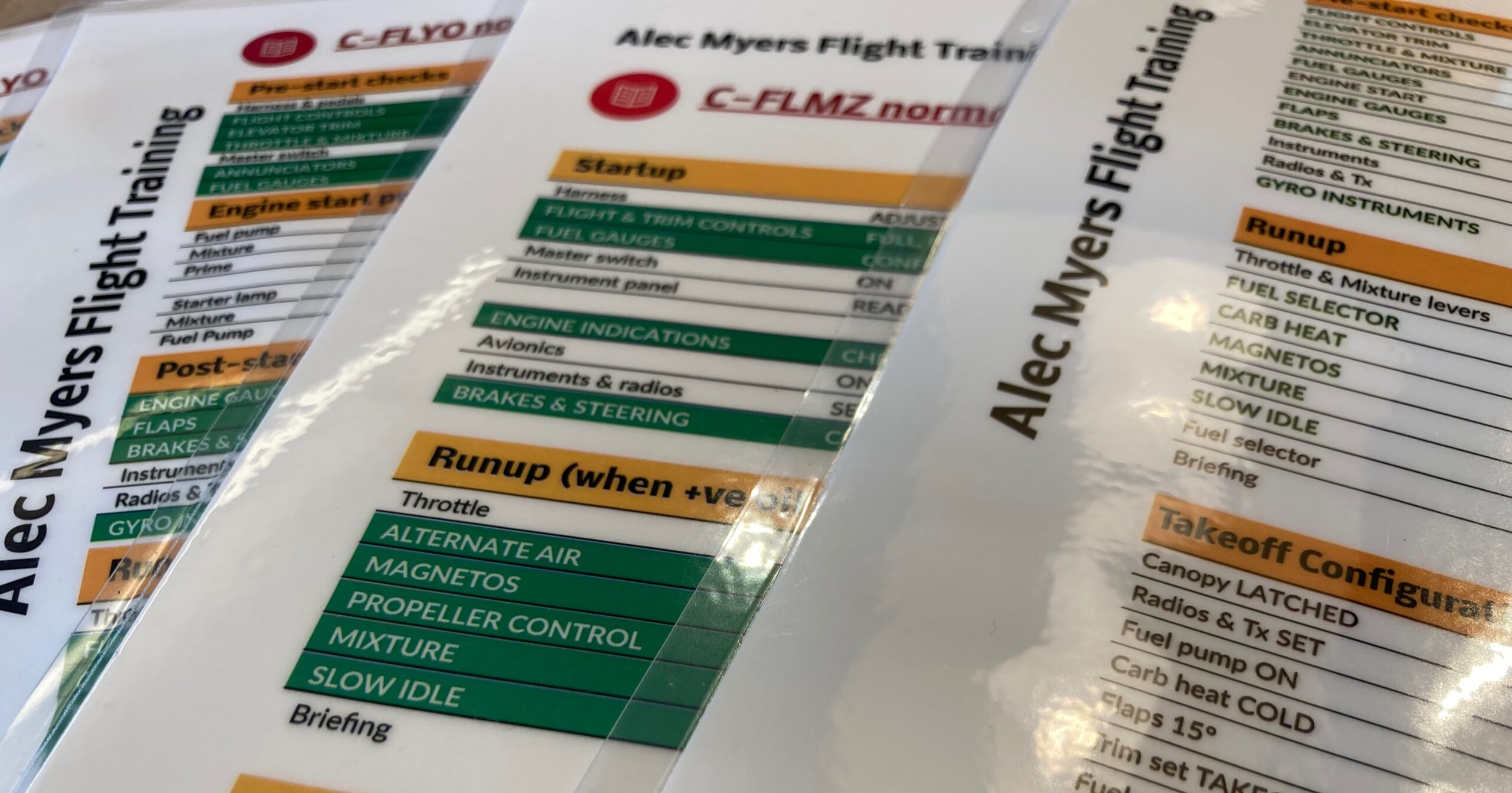

All recent student pilots will be familiar with the difficulties of the dreaded checklist – that innocuous spiral-bound booklet or laminated sheet of terse instructions and checks whose contents torture and haunt the start of every flight. I have a theory that a PPL flight test could be replaced by having the candidate explain to the examiner the purpose detail behind every item in their airplane’s checklist, and if the candidate got them all right they they pass their test, no flying required. I actually think it takes longer and requires more knowledge to properly understand the checklist for an airplane than it does to fly it – so if you can do the former you should get to do the latter as of right.

How have we allowed this state of offairs to come to pass? It seems to me that the simple airplane checklist is product of several different (and sometimes contradictory) requirements, which makes it inevitable that it fails to meet at least some of them as well as it could – just as the servant of two masters is bound to disappoint one or the other at some time.

What is a checklist for?

Let’s first survey the roles we ask our humble checklist to fill. I may have missed some, but these ones are obvious to me:

1: Something to make sure the pilot hasn’t missed any important step in setting up their airplane for takeoff/landing etc.

It’s possible to attempt most elements of flight with the airplane set up in such a way as to doom that attempt to a dangerous failure. As a response to human frailty we decided to write some of this possible missteps down and ask the pilot to check each element has been actioned correctly. That is, the list is a true check-list – of items to check. Example: make sure the flaps are set for take-off, prior to lining up with the runway.

2: a list of things to test prior to or during flight

Airplanes are complex collections of interconnected systems. Some of these systems admit to simple tests to verify they’re working accordging to expectation. A failure of a simple test informs us that the aircraft isn’t airworthy, and we shouldn’t fly in it. We collect a list of these simple tests and call it a check-list – a list of systems to check. Example: observing the RPM drop switching from both magnetos to one, and then the other, gives confidence (on seeing the expected result) that the magnetos are functioning properly. Caveat: the system can pass the test and still be defective. I remember one departure in a single engine cessna – following a successful run-up test – where the one defective magneto resulted in a significant power deficit on the “both” and such violent rough-running that the engine threatened to depart the airframe when set to the defective magneto alone – but only at full throttle. Failing the ground test means there’s a problem. Passing the ground test doesnt mean there’s no problem.

3: Something required to satisfy regulation 602.60(1)

Canadian Aviation Regulation 602.60 reads as follows:

602.60 (1) No person shall conduct a take-off in a power-driven aircraft, other than an ultra-light aeroplane, unless the following operational and emergency equipment is carried on board:

(a) a checklist or placards that enable the aircraft to be operated in accordance with limitations specified in the aircraft flight manual, aircraft operating manual, pilot operating handbook or any equivalent document provided by the manufacturer;

I think we’ll come back to this one later, but for now, just note that you have to have some kind of checklist or placards on board, and (not quoted here) (2) and (3) of the same regulation gives a minimum list of circumstances that have to be referred to in the checklist (pre-start, pre-takeoff, post-takeoff, pre-landing, emergency) and (4) says you have use said checklists when they are applicable.

4: Something to teach students how to accomplish one or more tasks

Student pilots being new pilots, they often find it helpful to have step-by-step instructions for how to fly a plane. Flying by numbers, you might call it. Actually manoeuvring the airplane by reading instructions from a list can be tricky, but one example that can be made to work is for the task of starting the engine: master switch on …. unlock fuel primer … prime three times … lock fuel primer … advance mixture … apply brake pressure … call “clear prop” … turn key to start …

5: Something to allow the manufacturer/regulator/operator to escape liability in the event of a problem

It seems to me that from an operational point of view small airplanes must be really badly designed, and the design is getting worse rather than better, because the number of things the manufacturer inserts into the pre-takeoff checklist gets longer and longer as the years go by. My 1939 Luscombe 8E didn’t have a checklist, at least not as far as I know. The 1968 operator handbook for the Cherokee 140 I have has 3 items on the pre-start checklist. By 1978, the pre-takeoff checks for the Cessna 172N numbered 6, The 1994 Grob has 18 items, and the DA40 from 2000 has 22 items. I concede that a DA40 is a more sophisticated airplane than a Luscombe but while a lot of design effort seems to have gone into making the generic airplane faster and more capable not enough has been dedicated to making it simpler to operate.

As an example – let me quote from the the DA40 pre-start checklist which requires the pilot to make sure the “Essential Bus switch” is “OFF, if installed” – for he or she should certainly have “CAUTION” that “When the essential bus is switched ON, the battery will not be charged unless the essential tie relay bypass (OAM 40-126) is installed.“. If you takeoff with the switch in the wrong position and have a horrible and damaging end to your flight as a consequence then – it must be your fault – you were warned. You were even warned about the technical reason – right there in the checklist. As well, you are informed about the manufacturer’s mitigation strategy for the danger – that essential tie relay bypass – right there, in your checklist. Does anyone else think that level of detail has no place in an operational checklist? Or is it just me?

How are these four checklist purposes at odds with each other?

It should be pretty obvious that a checklist that’s superb at one of these tasks is going to suck at the others. If your checklist was designed by lawyers it’s going to focus on keeping the manufacturer out of trouble. That’s accomplished in one of two ways: a massively conservative checklist that through its sheer length encourages the pilot to stay home because they don’t have the emotional energy or the attention span (or bladder capacity) to start at the beginning and work through to the end without messing up – or alternatively a checklist so long that pilots say to hell with it, and ignore half the elements on it. I note without further comment that the DA40 has thirteen pages of lists and instructions for the pilot to work through before they get to takeoff.

Similarly, if your checklist is written as an instructional aid then it’s also likely to be longer than it needs to be, containing detailed instructions for the benefit of the novice who needs them but which to the more experienced pilot just obscure the few items that they do need. There are only just *so* many ways to fire up a small Lycoming engine, and when the instructions to do so are written out in great detail they are likely to be ignored by someone who figures they know how to start a small Lycoming engine. Once you start skipping checklist items because “you already know it” then it’s easy to get into trouble by skipping the wrong things or too many things.

Write your own checklist

My preferred purposes for checklist are the first two: a list of systems to check prior to takeoff, and a check of how the aircraft should be configured for different phases of flight (typically takeoff, and landing) to be used after the pilot has done their best to achieve that configuration. That is, to be used as a real check list, and not a do-list.

I think it’s wise and sensible for pilots who fly their own airplane to produce their own checklists, based on their knowledge and experience of that particular plane and of others.

As a somewhat experienced operator of the small planes I fly, my preferred checklist for systems would be as short as this:

- flight controls, trim, throttle, mixture

- gauges

- brakes and steering

- instruments

- fuel selector

- magnetos

- carb heat

- mixture

- slow idle

I’m capable of working out when and where to test each of those items, and for each one I can remember how: I don’t need an explicit instruction to test the magnetos by switching from “both” to “left” then to “both” and then to “right” and then back to “both”.

Secondly, I might have a pre-takeoff configuration checklist, as follows:

- Canopy

- Radios

- Fuel pump

- Carb heat

- Flaps

- Trim

- Fuel selector

Those two lists cover everything I need to do before I takeoff in my small single-engine airplane, and they’ll both fit in one corner of a small card. Since they are short, I have a pretty good chance of working through them without losing my place or dying of old age, and I’m less susceptible to any very human desire to skip ahead, or just skip things by mistake.

What if I’m not me but a student pilot, instead? Unless I’m very familiar with the airplane those two lists are going to be too short. At a novice level I’m going to want some more (written) instruction to accompany. How do I test the carb-heat? What is the correct flap setting for takeoff?

So what you put in your checklist does depend as much on you, as on the airplane.

If you do decide to create your own checklists, here are some principles you might want to consider:

Start with the manufacturer’s checklists

Write out what the aircraft manufacturer thinks you should do and/or check for each normal operation and phase of flight. Identify the following themes:

- configuration items for the activity the list refers to: takeoff flap settings, mixture settings, the old “Essential Bus Switch” – that apply to your particular airframe

- actions that form part of system checks: sometimes several checklist items are part of making sure a single system is working. If you know how to do a mag check on a Lycoming engine then when these items appear in the manufacturer’s checklist you can condense them into a single entry when you create your own list.

- generic flying instructions that would apply to any aircraft, and which are general pilot knowledge. Your “take-off” configuration items list doesn’t really need to include an entry for “full throttle”, does it?

Collect together configuration items, and system tests. Discard general flying instructions. See if you can re-order system tests together, and configuration items together, if it makes sense to do so.

Try to have fewer different lists

CAR 602.60 mandates a checklist for at least pre-start, pre-takeoff, post-takeoff and pre-landing. See if you can avoid the need for a post-start and a pre-taxi list or any other extra phases by consolidating lists together.

Avoid repeated items

Some aircraft checklists repeat items. How many times do you need to check the elevator trim is set to the takeoff position? The danger with repeating items is that when you know something is coming up again later, there is a tendency not to take it seriously the first time. Each line in your checklist has a cost, in terms of time, and attention. Make sure each entry deserves its own real estate on the page.

Consider “optional” items carefully

Some checklist items are more-or-less mandatory from any point of view. You can’t get away without checking the carburetor heat operates correctly. But do you need to have “mixture rich” as part of a pre-takeoff checklist? Obviously you should follow the recommendation to takeoff only with the mixture fully rich, but does it need to be written down? If the mixture lever is right next to the throttle and you always treat the two together then it’s not likely you’ll omit to advance the throttle and leave the mixture behind. You may feel comfortable omitting a written “mixture full rich” item from your list pre-takeoff. If the mixture control is distant from the throttle so you can’t and don’t operate the two together then perhaps it does deserve to be checked in its own right before takeoff.

What about “transponder on”? Should radio configuration appear in a checklist? Again I think that depends on your personal preference. The consequences of omitting to switch your transponder to “mode C” before takeoff are fairly limited, so you may feel comfortable not including that in your list. A shorter list is easier to follow, more likely to be completed without mistakes and reduces the length of time your attention is drawn away from what’s going on outside the airplane where it should be.

Order the items thoughtfully

When you have a list of items to include in your checklists, pick an order in which to place them that has a logical flow to it. If your hands have to touch seven controls prior to takeoff, list them in an order that leads your hands logically around the cabin, for example left-to-right and top-to-bottom.

Flight test your lists

When you have your new checklists ready, flight-test them. Sit in the pilot seat and go through the list, first of all on the ground with the engine off – then, when you’re happy, use your list for real for a few flights. See what feels logical and what’s out of place. Don’t be afraid to move things around or re-evaluate some of the decisions you made.

Re-evaluate periodically

Writing a good set of checklists is not a one-off activity, done once for all time. As your knowledge and understanding of your airplane grows – and as you get some experience of what mistakes you are more likely to make – your decisions on what items to include in your checklist, how you word them, and what order to list them – are likely to change.