My sparge pump indicator isn’t working. Am I legal to fly?

by

Posted

Recording a defect

Before we get into the details, let’s back up a step. Let me remind you about CAR 605.94 which imposes on the Pilot in Command the obligation to record in the Journey Log any defect that arises in flight. Specifically it says:

605.94 (1) The particulars set out in column I of an item in Schedule I to this Division shall be recorded in the journey log at the time set out in column II of the item and by the person responsible for making entries set out in column III of that item.

And the relevant entries in columns I to III of Schedule I are:

- Particulars of any defect in any part of the aircraft or its equipment that becomes apparent during flight operations

- As soon as practicable after the defect is discovered but, at the latest, before the next flight

- The pilot-in-command of the aircraft

So make sure you follow that rule – record defects in the journey log – before you engage on the analysis below, about whether you can still fly or not.

Minimum Equipment

If your airplane is a small one like a Cessna 1xx series or a single engined Piper and you operate it privately, you won’t have an approved Minimum Equipment List. That means you turn to CAR 605.10 to see the following:

605.10 (1) Where a minimum equipment list has not been approved in respect of the operator of an aircraft, no person shall conduct a take-off in the aircraft with equipment that is not serviceable or that has been removed, where that equipment is required by

-

(b) any equipment list published by the aircraft manufacturer respecting aircraft equipment that is required for the intended flight;

-

(c) an air operator certificate, a special authorization issued under subsection 604.05(2), a special flight operations certificate or a flight training unit operating certificate;

If that seems difficult to interpret to you, you are not alone. if we look in CARS Standard 625, specifically 625.10, there is a long information note provided by Transport Canada on how to interpret 605.10. It begins, “The following provisions, although considered advisory in nature, have been included in the main body of these standards due to their importance.”

Two sections from the note in 625.10 are worth highlighting here:

(i) CAR 605 requires that all equipment listed in the applicable airworthiness standard, and all equipment required for the particular flight or type of operation, must be functioning correctly prior to flight. The requirement for a particular system or component to be operative can be determined by reference to the type certificate data sheet, operating regulations or the applicable equipment list in the aircraft operating manual.

That gives us some strong guidance on how to interpret 605.10. Also very relevant:

(ii) Although the responsibility for deciding whether an aircraft may be operated with outstanding defects rests with the pilot in command, an error in this determination could result in a contravention under these regulations.

This is telling us that the Pilot in Command has to make the final decisions, but they had better make the right decisions. A contravention of 605.10 can be punished with a fine of up to $5000 per flight, for individual owners!

Standards of Airworthiness

Now let’s turn back to the regulation. Here’s how I interpret paragraph 605.10(1)(a), in respect of our hypothetical sparge pump indicator. The phrase “standards of airworthiness” refers to the regulations under which the aircraft was certified to be airworthy. If you look at the type certificate data sheet (TCDS) for your aircraft it will have a section called “certification basis”, and that’s where the standards of airworthiness are described.

To take an example, let’s suppose the aircraft in question is a 1975 Cessna 182 Model P. the TCDS for the Cessna 182 lists the certification basis as

Part 3 of the Civil Air Regulations dated November 1, 1949, as amended by 3-1 through 3-12 and Paragraph 3.112 as amended October 1, 1959, for the Model 182E and on. In addition, effective S/N 18266591 through 18268586, FAR 23.1559 effective March 1, 1978. FAR 36 dated December 1, 1969, plus Amendments 36-1 through 36-6 for Model 182Q and on. In addition, effective S/N 18268435 through 18268586, FAR 23.1545(a)Amendment 23-23 dated December 1, 1978.

That means we need to look at Part 3 of the (United States) Civil Air Regulations, as amended at October 1, 1959. CAR 3, was replaced by FAR23, but you can still find them online in various places, for instance here. The FAA also has a helpful webpage with a summary of updates to CAR3 here.

Alternatives to CAR3 are FAR23 if you have a more modern airplane with a US type certificate, or CAR523 if your airplane has a Canadian type certificate.

So if, somewhere in those details, it says that a sparge pump indicator is required for flight by day, night, VFR or IFR – whichever your prospective flight involves – then you can stop there, because you know your aircraft isn’t airworthy. Luckily for us, I happen to know that the sparge pump indicator wasn’t invented until 1992, so it couldn’t possibly be included in airworthiness requirements dating from the 1950’s. So we’re good to move on to the next section.

Manufacturer’s list

Paragraph (b) of 605.10(1) says that if your sparge pump indicator is included in any list of equipment the manufacturer says is required for your flight – day, night, VFR or IFR as appropriate – then your aircraft isn’t airworthy.

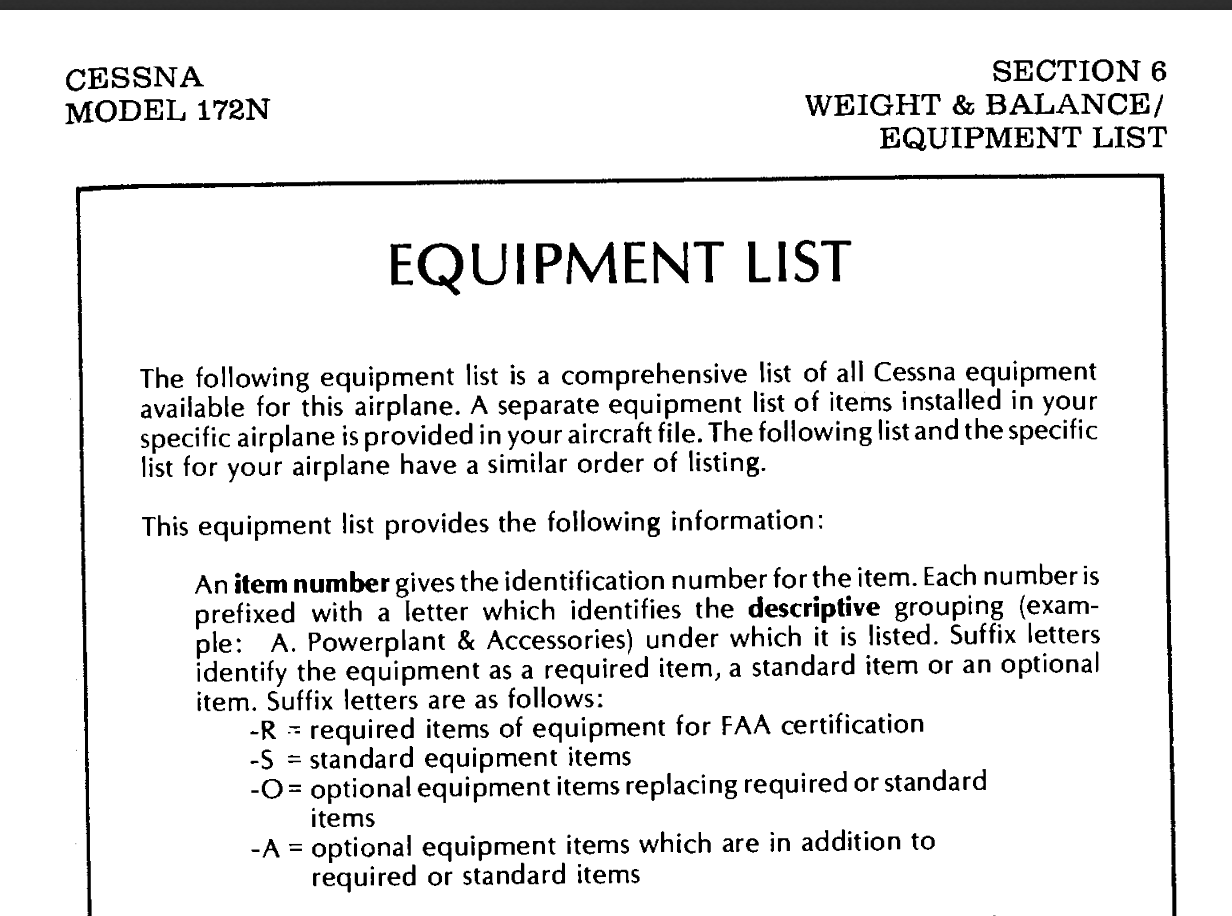

Where do you find such a list? The most likely place is in the Pilot Operating Handbook or Approved Flight Manual. For example If you look in the POH for many small Cessna airplanes the equipment list in Section 6 records items as Required, Standard, or Optional:

If the sparge pump indicator is listed on the subsequent pages with a suffix “-R” that would be a good indication that it meets the condition in 605.10(b) and so your aircraft isn’t airworthy. If it’s listed as “-O”, “-S” or “-A” then you pass the test, and we can move on to 605.10(1)(c).

Air Operator’s Certificate, FTUOC …?

As a private aircraft owner you’re not operating under any kind of operators certificate, and nothing in section 604 of the CARS applies to you. So you get a free pass on 605.10(1)(c).

Airworthiness Directives

Now we’re on to 605.10(1)(d): Airworthiness Directives are after-the-fact modifications to the the aircraft certification basis, usually in terms of required inspections or maintenance, but it’s possible that some AD mandated that the sparge pump indicator be added or required for some or all conditions of flight. If so, then clearly you can’t fly without it in operational condition.

These Regulations

Nearly done – we’re on to 605.10(1)(e), the last bit. Some parts of the CARs require certain kinds of operational equipment for different categories of flight. For instance CAR 605.14 lists the required equipment for day VFR flight – it’s the list that every student learns for their flight test (tach, oil pressure gauge, fuel gauges, altimeter, compass, air speed indicator…) and 605.16 adds various items for night VFR. Neither of those list (nor any other CAR requirement) demands a sparge pump indicator, so it looks like we’re home and dry. There’s no regulation that forbids us to fly with our aircraft in this condition, and if it’s not forbidden, it must be allowed.

But wait…

That’s not the end of the story, because the rest of CAR 605.10 reads as follows:

(2) Where a minimum equipment list has not been approved in respect of the operator of an aircraft and the aircraft has equipment, other than the equipment required by subsection (1), that is not serviceable or that has been removed, no person shall conduct a take-off in the aircraft unless

(a) where the unserviceable equipment is not removed from the aircraft, it is isolated or secured so as not to constitute a hazard to any other aircraft system or to any person on board the aircraft;

(b) the appropriate placards are installed as required by the Aircraft Equipment and Maintenance Standards; and

(c) an entry recording the actions referred to in paragraphs (a) and (b) is made in the journey log, as applicable.

Even if we don’t need the equipment to be working, in order to be legal we first have to isolate, secure, or remove the equipment so as not to constitute a hazard. What does that mean? It depends on what the equipment is. There’s a certain level of judgement to be exercised here, and if you’re not confident you’re making the right call then you should definitely consult a licenced Aviation Maintenance Engineer (AME) for advice.

If the item in question is a piece of rack-mounted avionics then its removal falls under paragraph 18 of CAR 625 Appendix A as elementary work that you as the aircraft owner can carry out on your own.

If it’s some kind of panel mounted gauge then you’re not permitted to remove it but you might reasonably decide that even in its inoperative state it doesn’t constitute a hazard (to any other aircraft system or person on board) and therefore doesn’t need to be isolated or secured. Otherwise, you could take advantage of the elementary work task described in CAR 625 Appendix A paragraph (27) by yourself:

deactivating or securing inoperative systems in accordance with sections 605.09 or 605.10 of the CARs, including the installation of devices specifically intended for system deactivation, where the work does not involve disassembly, the installation of parts, or testing other than operational checks;

I interpret that as meaning you’re permitted, for example, to pull (and tie off) the relevant circuit breaker, or cover up an instrument.

If the work needed to make the system safe isn’t covered by that description then you will have to engage an AME to perform the maintenance action of securing, isolating or removing it, as appropriate.

Paragraph (b) requires that appropriate placards are installed as required by the Aircraft Equipment and Maintenance Standards. Those are CAR Standard 625 and the requirements for placards are in 625.05, which refers to the requirements in “the type certificate or aircraft flight manual;”. Looking at those documents there’s nothing relevant to a placard being required for an inoperative sparge pump indicator. Nevertheless, it seems to me to be prudent and a good idea to placard that something isn’t working, or has been removed.

Finally 605.10(2)(c) requires that a logbook entry is made to record any actions of isolating, securing or removing the inoperative equipment and the installation of a placard. If you undertook the work yourself as elementary work you should make a Journey Log entry yourself, otherwise make sure the AME who helped you makes the entry.

If you follow those procedures then I think it’s unlikely that a Transport Canada inspector will take issue with your determination that your aircraft is airworthy and your decision to fly.

Finally…

It’s worth looking at CAR 605.08:

605.08 (1) Notwithstanding subsection (2) and sections 605.09 and 605.10, no person shall conduct a take-off in an aircraft that has equipment that is not serviceable or from which equipment has been removed if, in the opinion of the pilot-in-command, aviation safety is affected.

(2) Notwithstanding sections 605.09 and 605.10, a person may conduct a take-off in an aircraft that has equipment that is not serviceable or from which equipment has been removed where the aircraft is operated in accordance with the conditions of a flight permit that has been issued specifically for that purpose.

605.08(1) says that even if you think you’re allowed to fly with the (for instance) sparge pump indicator not working, if the PIC thinks that that safety would be affected, they must refuse to fly. Now if you’re the PIC it seems unlikely you’d disagree with your own determination, but if you wanted someone else to fly for you they have an extra option to justify their refusal.

And, more usefully, in this scenario – 605.08(2) says that even if the sparge pump indicator is required by one of the conditions in 605.10, if it’s not working and you really need to make a flight, say to somwhere you can get if fixed, you have the option of applying to Transport Canada for a flight permit – effectively special permission to make a flight or series of flights, under certain conditions (typically day VFR only and without passengers, or some other requirements).